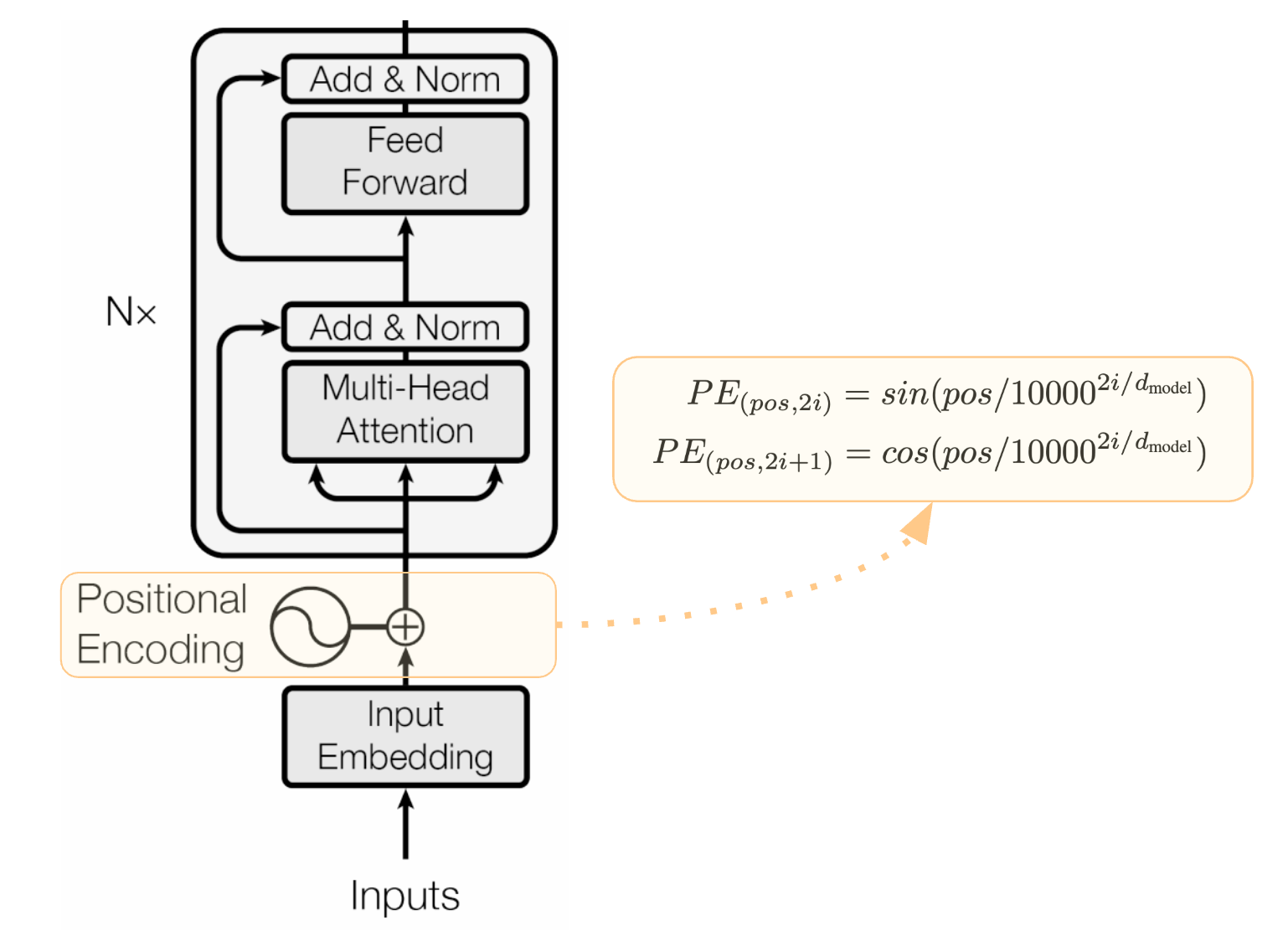

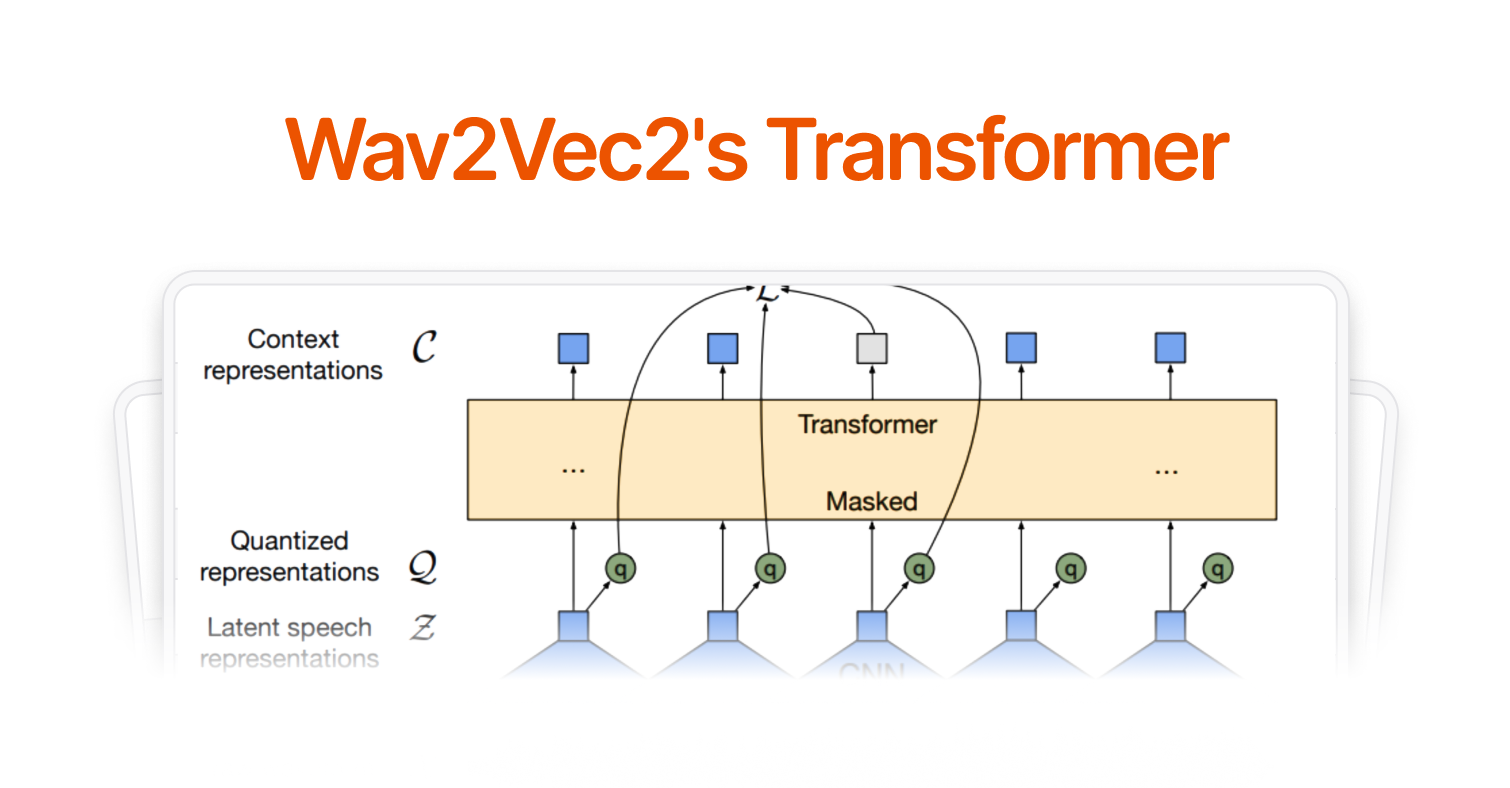

Typically, every explanation of the Wav2vec2 architecture begins with this iconic diagram (Baevski et. al). But without extensive background, it is hard to know how this yellow block compares to the traditional Transformer.

The Wav2Vec2 architecture distinguishes itself from other Transformer-based architectures largely in processing audio input and aligning the output. In our last article, we discuss Wav2Vec2's Feature Extractor: turning raw audio into feature vectors. Now we'll trace how Wav2Vec2 encodes positional information of sound in the Transformer and how it aligns its predictions to text.

Wav2Vec2 Transformer: Processing Input

Also called the Context Network, the Transformer processes feature vectors using self-attention, which lets each feature attend to all other features in the sequence.

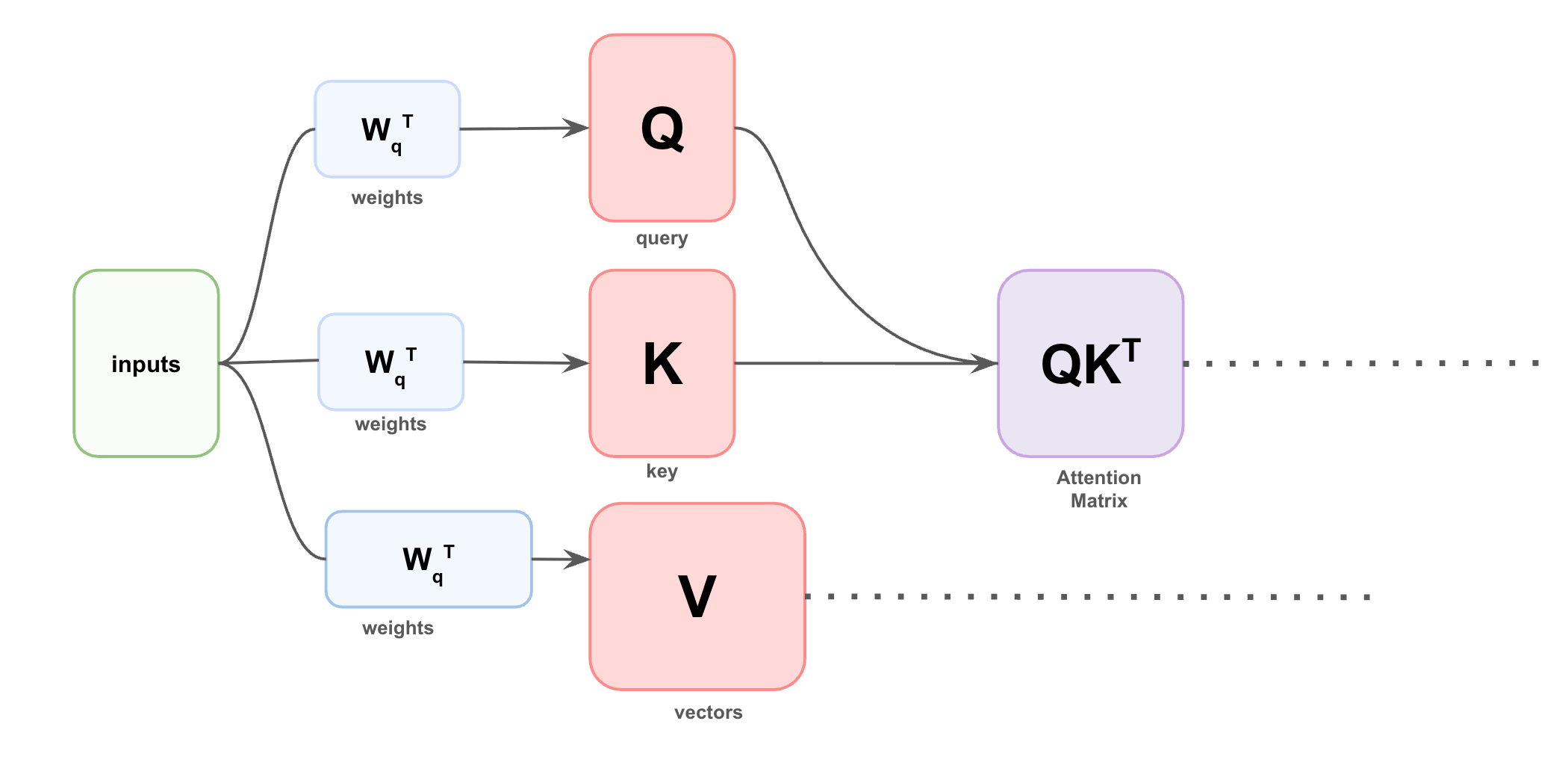

Visual glimpse into attention matrix computation of self-attention

But a critical challenge is that attention naturally ignores the order of the input sequence.

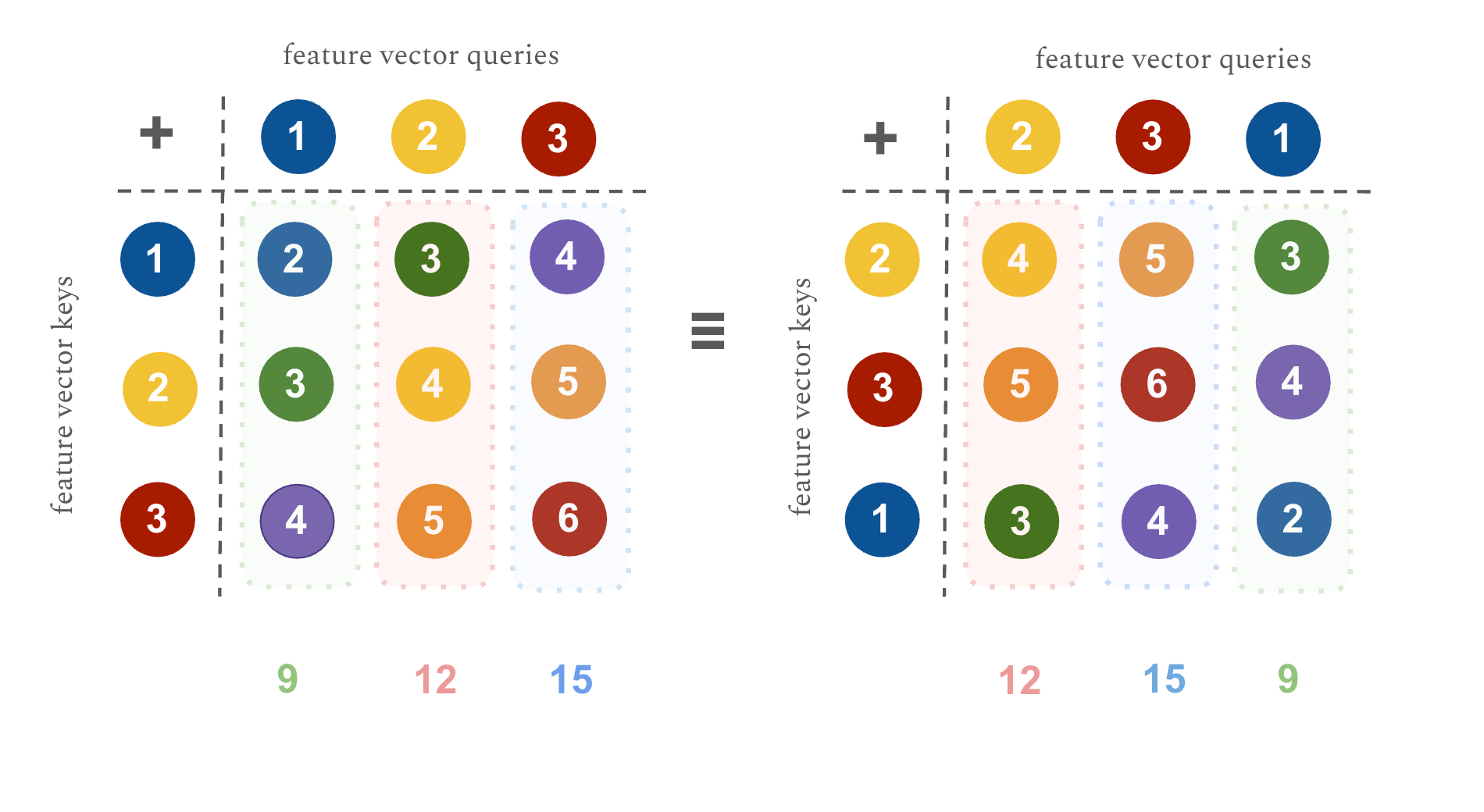

When we take the dot product of the query and key vectors, a different ordering of the input sequence can produce equivalent vectors. This goes back to the dot product being commutative.

We can look at another commutative operation as a toy example: addition. You can see that there is no way to distinguish a 1 in the very first position from a 1 in the very last position, the attention mechanism understands the sequences equivalently.

Why is this a problem?

The sounds we produce are often influenced by surrounding sounds. For example, in many dialects, a vowel before the “L” in “bottle” gets inserted, to create the syllabic “l̩” : “bottal”. Understanding each sound individually would likely mean that these syllabic sounds like “l̩” would be poorly predicted by the model. Surrounding consonants and vowels influence our speech making embeddings that encode these temporal relationships essential.

Positional Embeddings

Before we understand how Wav2Vec2 handles position, let's look at various attempts to develop positional embeddings. We will start with absolute positional embeddings.

The simplest approach is to give each position in the sequence a unique vector, almost like a name tag:

Position 0 gets vector A, Position 1 gets vector B, Position 2 gets vector C, …

But hardcoded positions are limiting. You can only have as many tags as the longest training example so generalizing to unseen, longer lengths during inference is difficult.

Sinusoidal Positional Embeddings

In an attempt to develop a method that could handle unseen sequence lengths, the authors of Attention Is All You Need introduced sinusoidal embeddings.

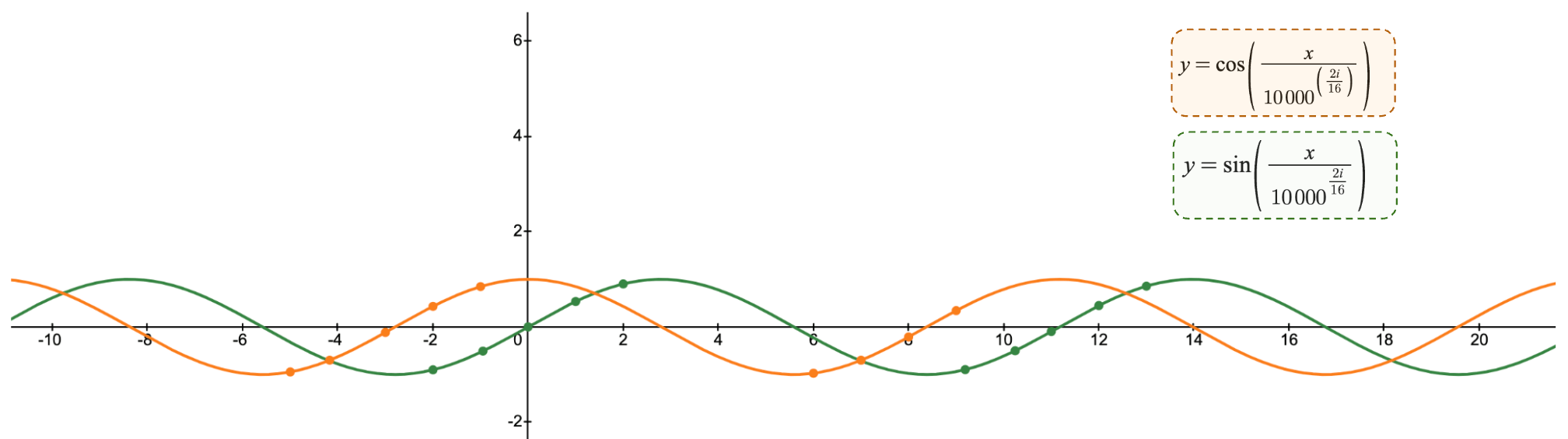

They use sine and cosine functions on even and odd positions, denoted as PE(pos, 2i) and PE(pos, 2i+1), respectively.

Break: Story Time

For an intuition of sinusoidal embeddings, let me tell you a story.

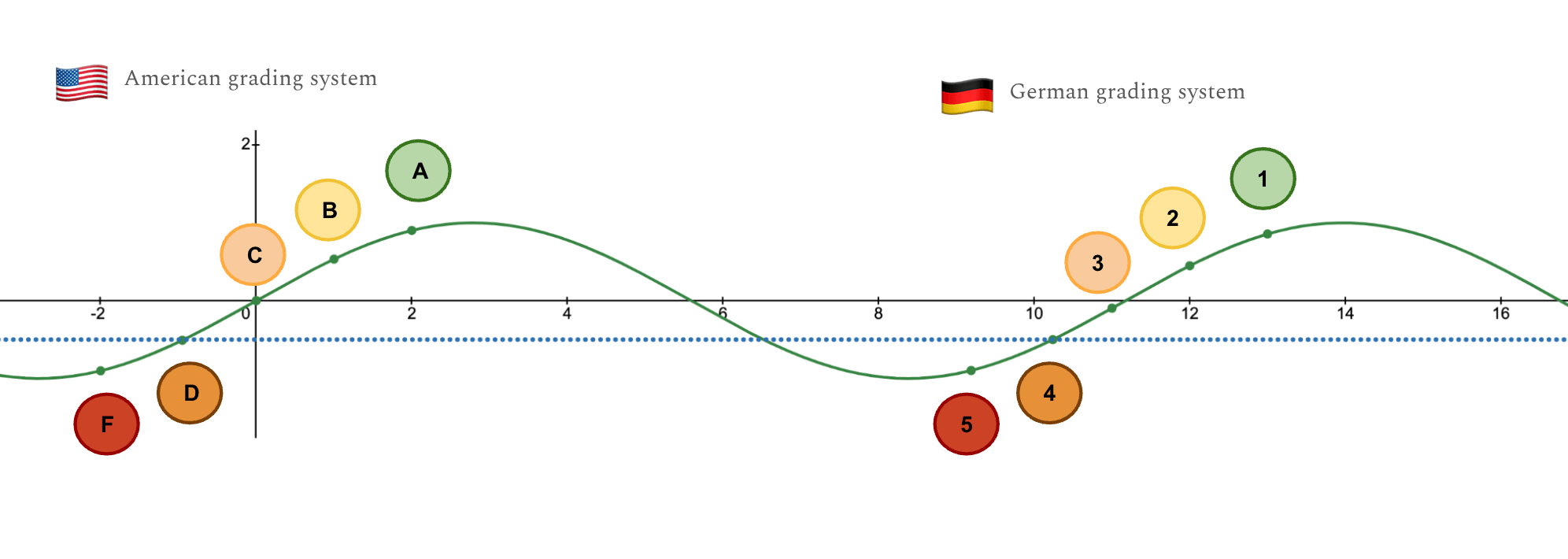

My friend Helen was attending school in Germany and told me that they did terribly in English class, she had gotten a 4! I laughed and said she was being dramatic: “A 4 isn’t bad at all!” To make her feel better, I told her: “I got a D in science”.

But then, she told me that a 5 was the worst grade you could get. Turns out, I was doing about as badly in science as she was in English…

Funny enough, our poor academics illustrate the sine function quite well. The sine function allows for strong local understanding. Within my American school system, my classmates all knew how grades compared: an A is better than a B, a B is better than a C. Within Helen’s German system, her peers also understood the relative order. So global distance is harder to understand but local relative distance can be well understood.

For a model that cares more about local distance, this function is very practical. Instead of giving every position its own unique number, which would quickly become unmanageable, they use a smaller set of values along a few smooth repeating functions. Note that the authors added cosine for additional expressability so more numbers could be represented but it follows the same principle as the sine function.

Sine and cosine functions for arbitrarily chosen dimension 16

Funny enough, Attention Is All You Need spent time adding in sinusoidal embeddings for it to perform identically to simple indexing.

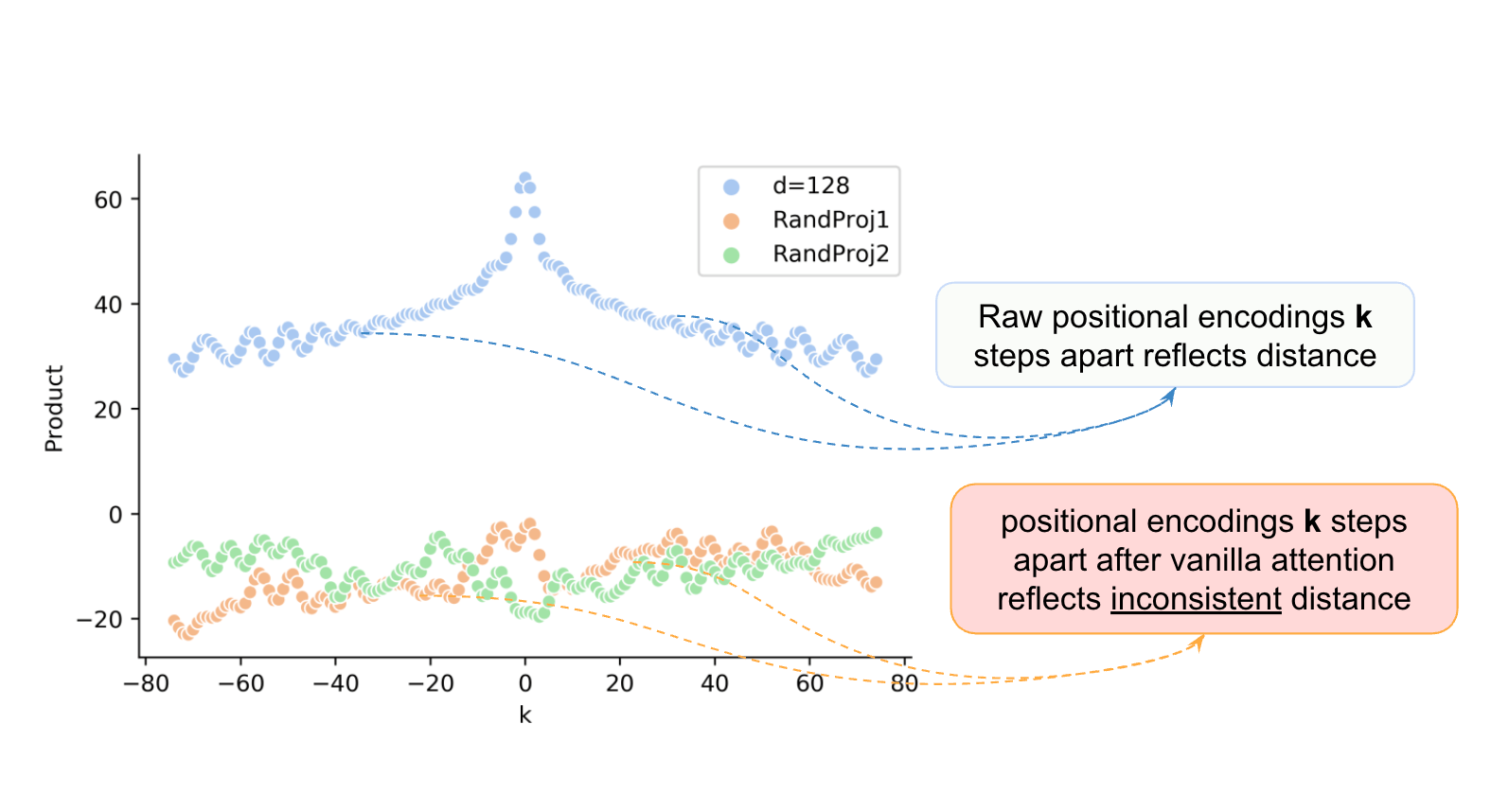

The challenge appears not to be formulating positional understanding but preserving it. Yan et al. finds that relative positional understanding in the input embedding gets destroyed during the attention mechanism when projected through the weight matrices (W_Q and W_K).

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1911.04474

In the Figure, (Yan et al.), distance information is preserved in the raw positional encodings (blue line) as shown by the symmetrical peak where positions close to each other (in the center) have a higher dot product . However, after multiplication by the attention weight matrices, we get seemingly random patterns (orange/green lines) that no longer clearly encode distance.

Limitations of Absolute Positional Embeddings

Both methods of absolute positional embeddings are limited by the fact that you can only recover positional information by some global lookup table telling you the sinusoidal values and simple indices which every feature corresponds to.

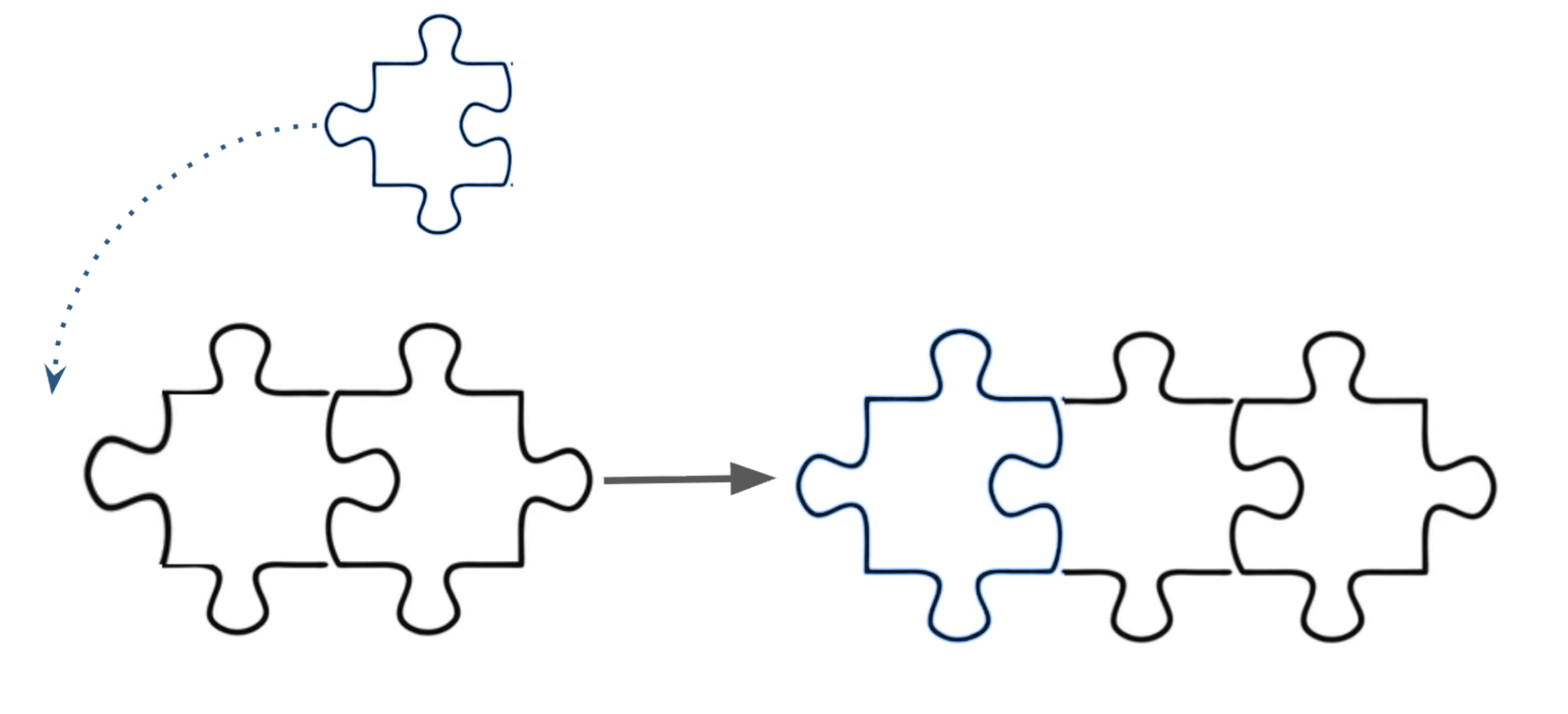

Instead, a good way to find the positional information of a feature could be to bake it into the feature itself. Positional information would be innate to the feature like a puzzle piece. Each piece has grooves from the neighboring pieces that inform you where it should go. Even though the puzzle piece does not have a number indicating its position, it can be determined where the puzzle piece belongs using other neighboring pieces.

Wav2Vec2 positional encodings

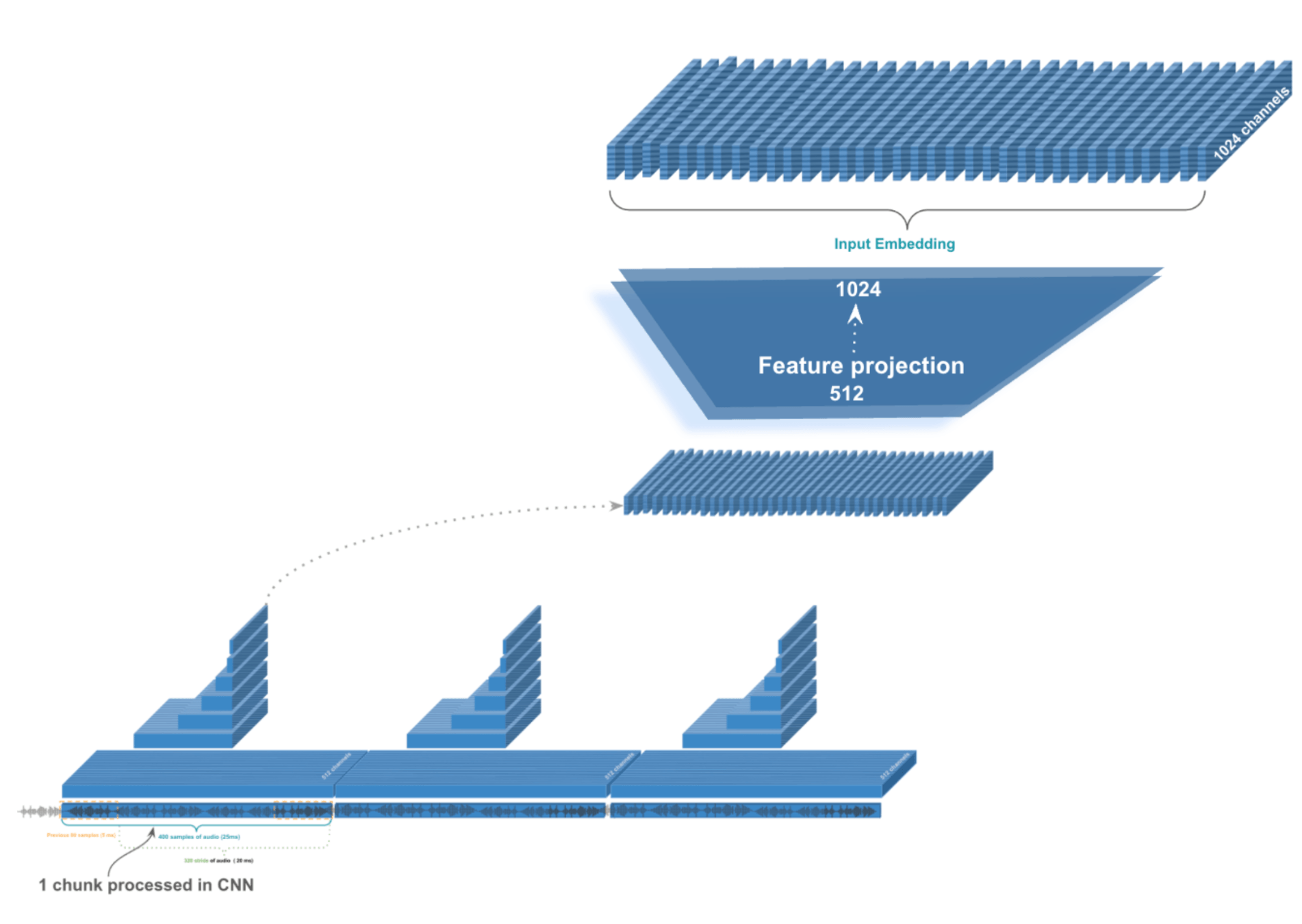

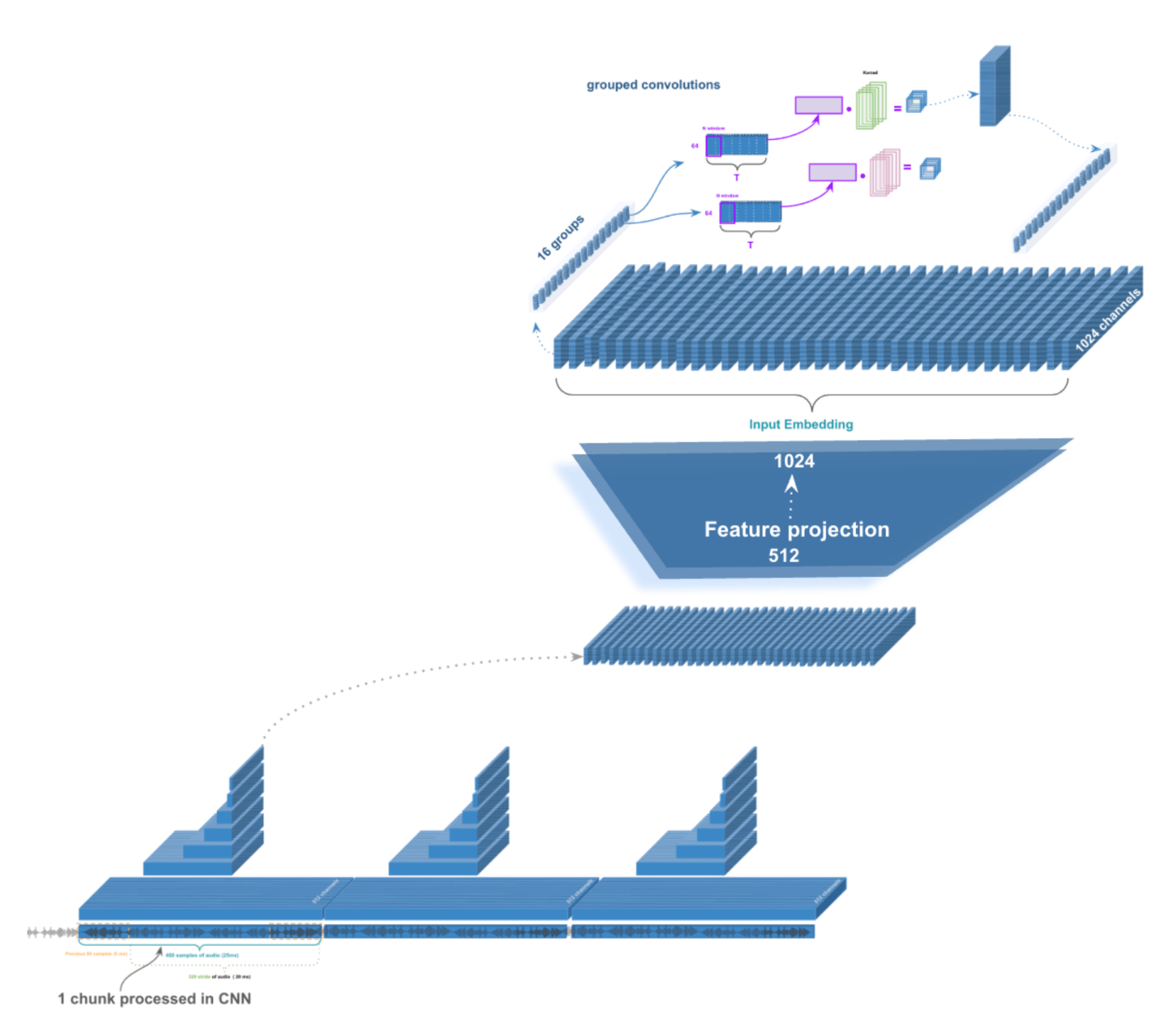

Wav2Vec2 accomplishes positional understanding by capturing local dependencies through convolutions at the input level, before features reach the transformer (methods like RoPE achieve similar goals by modifying the attention mechanism itself, but that's a story for another post).

As we covered in our previous post on the feature extractor (CNN), convolutions are used to naturally encode positions by using a sliding window over adjacent frames. They effectively represent relative local patterns like "a pattern across frames t-1, t, and t+1" rather than absolute global ones like "frame t with a position tag."

Likewise, convolutions can be applied to the output feature vectors after linear projection from the feature extractor for positional understanding.

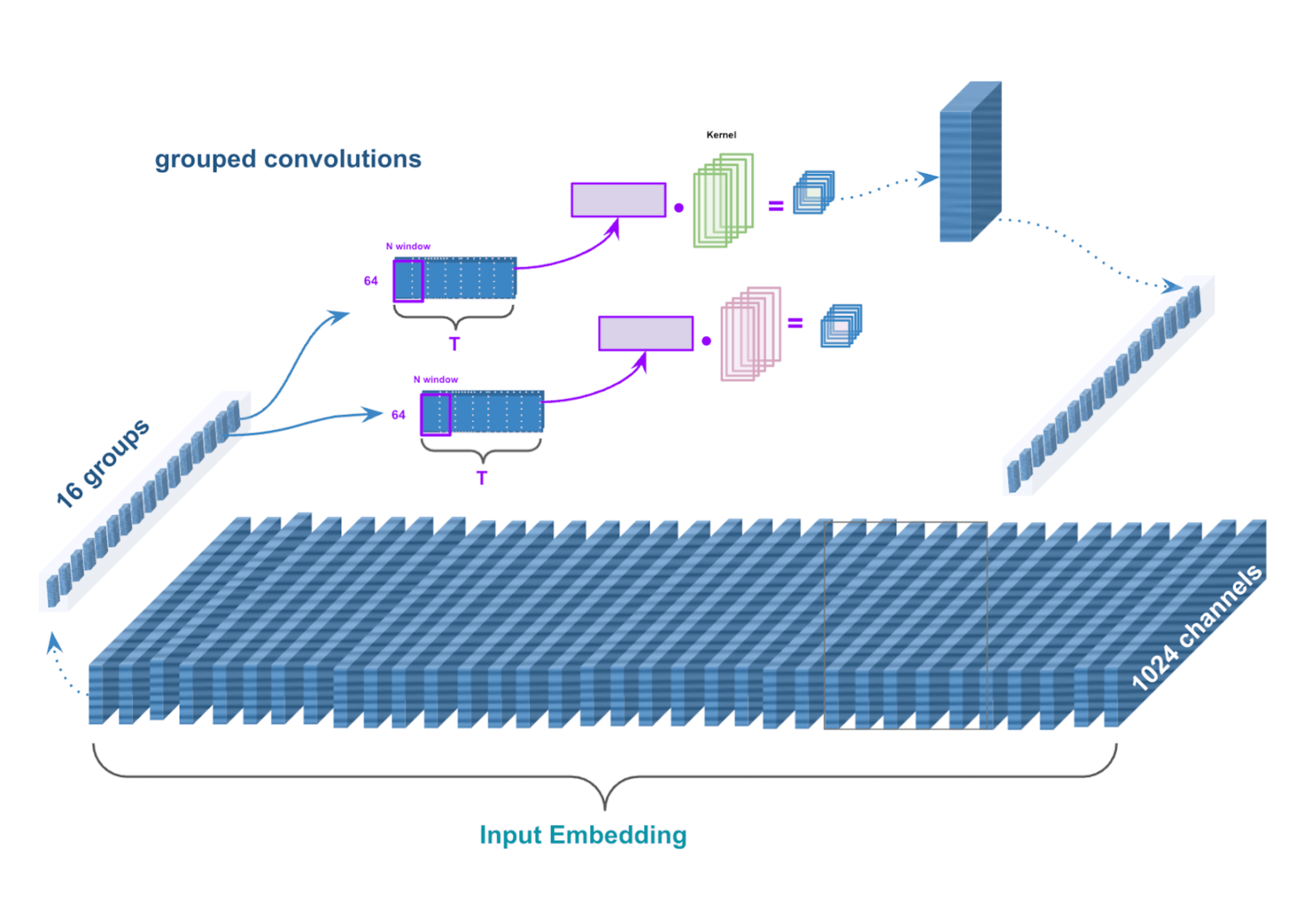

The wav2vec2 architecture uses grouped convolutions, where different groups specialize in different temporal relationships. Some might focus on quick changes between sounds, while others capture longer patterns like rhythm and intonation.

So now the positional information survives as it is intrinsic to what the feature represents. If a feature encodes "a rising pitch across three frames," that relational pattern persists through linear transformations.

From here, every 25 millisecond frame processed has positional information that the Transformer processes, outputting a single token prediction.

But this creates obvious problems: people don’t speak one character every 20 milliseconds! For example, the “o” in “hello” probably takes ~1/10th a second which is 100 milliseconds, much more than 20 milliseconds.

Finding what parts of the audio correspond to the predicted transcription is quite challenging. The audio datasets the model is trained on will (most of the time) not include timing information that says which word or syllable occurs where in the audio file because annotating this is super labor intensive. How will we know how to align the sequence to text?

CTC Loss: Aligning The Output

Training with CTC Loss:

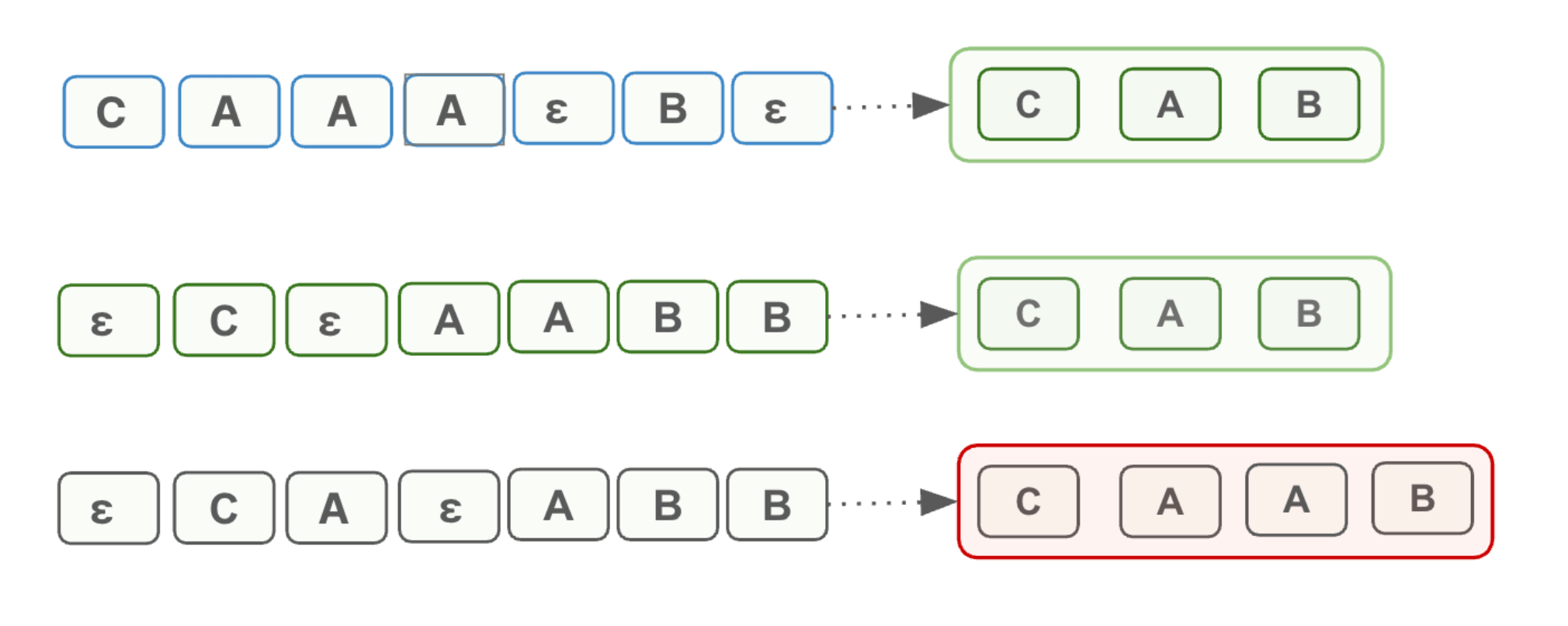

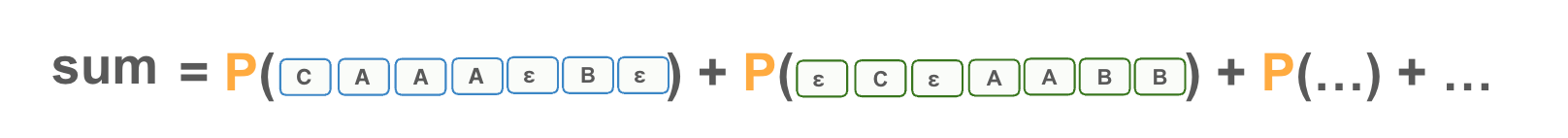

Goal: Train the model to assign high probability to paths that match the target sequence as shown below.

Note that we will “collapse” sequences by merging repeated characters and dropping the ε character:

The challenging part of this task is that there are many ways to predict this distribution such that you collapse to the correct target sequence. For example, “CAAB” and “εCAεB” both collapse to “CAB”. So how do we train a model with a multitude of possible sequences?.

Your intuition may be to sum across the probabilities of paths that produce correct sequences.

Not a bad idea! But this will just give us some arbitrary number like 5.76 which is hard to know how well the model is performing.

In an ideal world where the model has 100% certainty of the path that produces a correct sequence, it should receive 0 penalty. Likewise, if the model is very uncertain but still produces a correct sequence, it should receive more penalty.

It is like a multiple choice exam, two students can score well but one may have guessed more than another. If we know each student’s own personal certainty can we write a function that reflects this?

Easy! We use the function -log(x). For certainty of 1, we have penalty -log(1) = 0. Likewise for low certainty like 0.2, we have penalty -log(0.2) = 0.69

Nice! This is a good loss function for training.

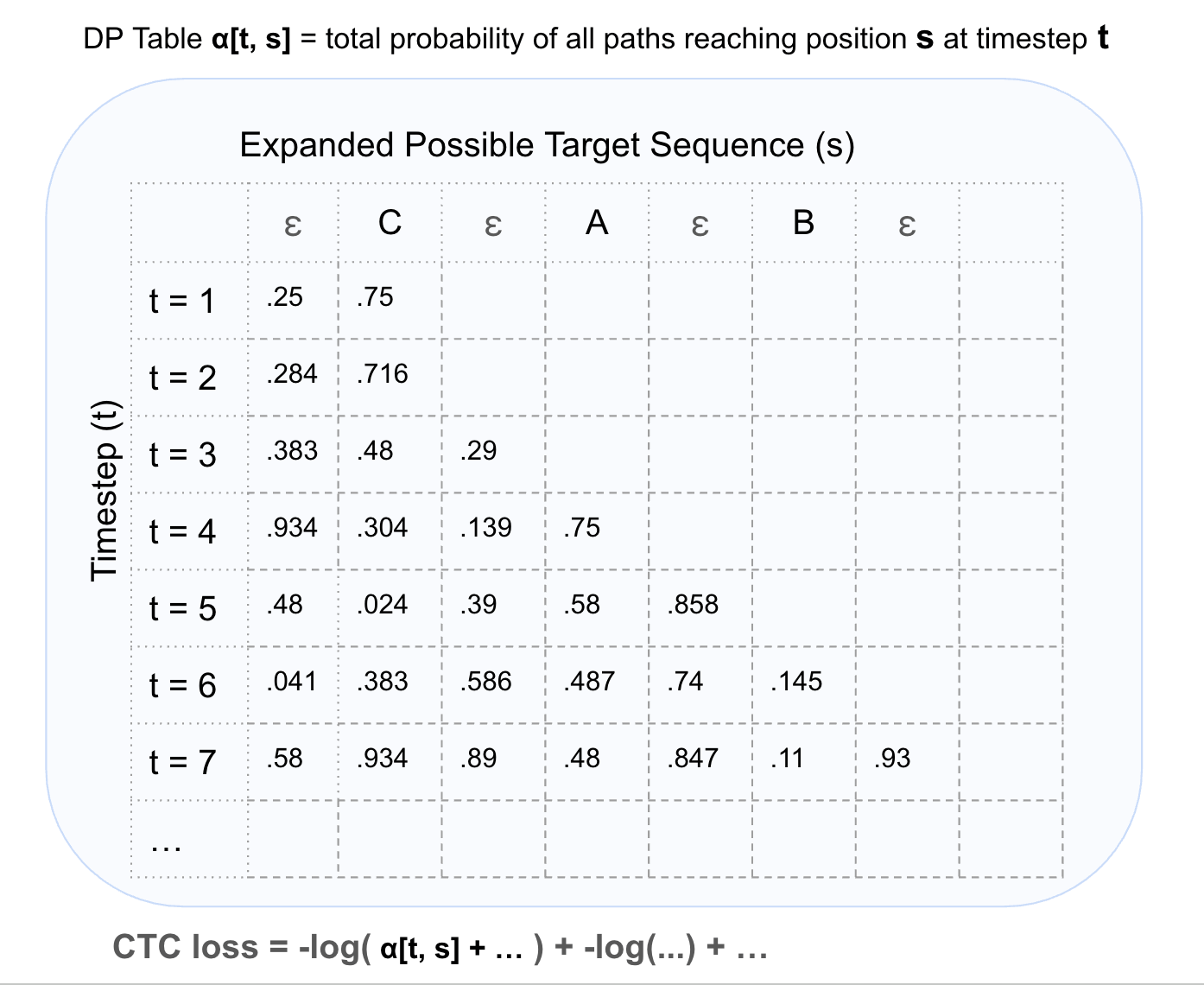

Efficiency

But a brute force approach to sum path probabilities as illustrated above would be very slow. Dynamic programming can be used instead where we use memoization to store total probabilities at each timestep. Here is what the DP table could look like:

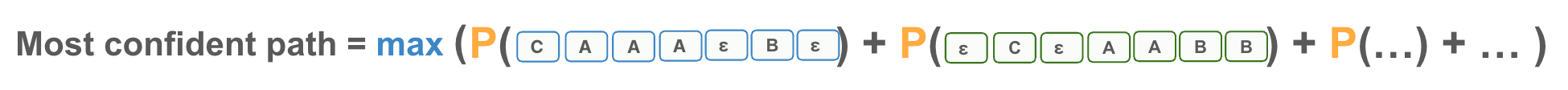

Inference with CTC Loss:

Goal: Given the trained model’s outputs, find the most likely text sequence.

We could simply use greedy search to grab the maximum probability at each timestep, but greedy makes locally optimal choices that can miss the globally best path. A slightly lower probability token now might enable much higher probabilities later. So, a modified beam search is used to optimally find the best sequence even when you have multiple possible alignments mapping to the same output.

So this modified beam search on the CTC head outputs allows us to find our final output!

Conclusion

To summarize, we started with a fundamental problem: attention mechanisms don’t naturally understand order. To fix this, Wav2Vec2 uses convolutional positional encodings that capture local context in sound rather than absolute positions (crucial for variable-length audio and how adjacent sounds influence each other).

Then we tackled the alignment challenge. Without knowing exactly when each character appears in the audio, CTC provides an elegant solution: consider all possible alignments, predict at regular 20ms intervals, use blank tokens for silence, and collapse duplicates during decoding.

By focusing on relationships rather than absolute positions, and probabilities rather than hard alignments, Wav2Vec2 can learn from audio at scale.